When Writing Fantasy, Kill Your Darlings. Literally.

How to kill your characters to achieve maximum story efficiency.

"Murder your darlings." - Arthur Quiller-Couch (Though many have said similar sentiments.)

My family has been watching the second (and final) season of Arcane on Netflix. Arcane is a TV-series version of the video game League of Legends. Thus, by all the Laws of Nature, it should be unwatchable. Yet, shockingly, it is pretty good.

The great joy of Arcane is that its creators are keeping it short. A total of 18 episodes. Around 11 hours. Whether this is for artistic or budgetary reasons does not interest me. Eleven hours is enough time to tell just about any story.

This is great because it gets us into the last season quickly. If you are writing a fantasy epic, unless you really seriously blow it, the last season is going to be awesome.

(Yeah, yeah. I know. The last season of Game of Thrones was infamously terrible. Bear with me. I'll get to that.)

Why is the last season generally great?

Because you get to kill everyone and blow up the world. Arcane is killing characters left and right, and that enables good fantasy.

We Take Fantasy Seriously

I have made my living for 30 years as a fantasy author, albeit in a pop culture variant. I do take it seriously.

Fantasy and fables strip away the mundane annoyances of everyday human life. Instead, fantasy conveys the values of the society that makes it. That's why we tell fantasy stories to children so often.

I've written in the past about how fantasy has been a default mode for human storytelling since forever. And how modern fantasy can fail to satisfy us when the moral underpinnings of the setting and the story you're trying to tell no longer match. (Did you know they made a second season of Rings of Power? It did not make a splash.)

So when you write fantasy, death is very important. When a character in a fantasy dies, it reflects two things. One: What that society sees as the greatest dangers. Two: What a society thinks is worth dying for.

That's a huge topic. Right now I'm more focused on practical matters: How to kill your characters for best effect.

Your Characters Are Like Money

When writing long fantasy epics, one of the great joys is blowing everything up at the end. When you make a sand castle, only half of the joy is in the creation. The other half is in its destruction, either by the waves or by just jumping up and down on it.

When you write a huge story, you are going to develop a lot of characters. The main protagonists and antagonists, of course. But these are supported by a somewhat larger number of secondary characters. Which are, in turn, layered over a host of minor characters. Plus, of course, settings, religions, magic items, etc.

It's a lot of work developing all these elements. You get something in return. When you put in time and work developing "Bob, The Loyal Blacksmith," and then you force your customer to learn about Bob, you have developed something of value. Bob is now money.

What is the point of money? To spend it. You now have earned the right to find a good time to kill Bob.

(Of course, you don't have to kill Bob. Maybe Bob is rewarded for his service to his king by getting to marry Elspeth, The Hot Tavern Wench. YAWN. Anyway, Bob can't marry Elspeth. She's getting super-stabbed during the surprise orc raid at the end of Book Two to give everything moral weight.)

Spend Your Money At The Right Time

Whenever you have a big story beat, you can add emotional emphasis to it by killing a character. Or five characters. The more characters you kill, and the more developed those characters are, the greater the impact. If you do it right, your slight "Let's go kill the evil demon with the elf sword" story starts to develop real emotional heft.

Killing a character in your book does all sorts of good. The reader gets put in suspense. The reader feels emotions. The reader has one less character to remember the name of.

However you don't want to waste your money. Don't kill characters too fast, or you run out and the customer feels numb. Don't do it too slow, or there's too many characters clogging your work and not enough stakes.

Some instructive examples ...

Example 1: Disney Anything

At one end of the extreme, we have Disney. Modern Disney films never kills a character if it can possibly be avoided. Even in a film that is explicitly about dealing with death, like Soul, there will always be a cheap trick to push a character's inevitable end until after the credits roll.

Interestingly, Disney films rarely have villains anymore! Their movies are so wimpy that they can't even kill a bad guy.

This is just my opinion, but: Disney and Pixar movies are no longer events in the way they once were. I think that, for the last decade or so, they've been churning out a whole bunch of really flat movies. Disney releases flops with a frequency considered unthinkable a decade ago.

My unsolicited advice: In their next movie, they should develop a nice character and then kill it. One Bambi's Mom would create enough suspense and interest to carry through ten wimpy movies.

Example 2: Game of Thrones

Many readers will be familiar with Game of Thrones, a series of fantasy novels by George R.R. Martin that will never be finished. The trademark quality of the series is that major characters frequently die, usually in spectacular, gruesome, nihilistic set-pieces.

If you read the third book (or watched Seasons 3-4 of the show), wasn't that AWESOME? Tons of the coolest characters going splat all over the place! One of the massacres was so spectacular that people started calling it the Red Wedding and it has its own page on Wikipedia!

Then the fourth and fifth books came out, and it turned out the heart had been ripped out of the thing. The dead characters were the people readers cared about. Worse, they were also the only ones who could move the plot along. The secondary characters who got promoted to replace them just weren't sufficiently interesting. Martin expended too many of his characters too quickly.

(The TV series was deeply flawed, but it did take the tangled mess of the books and turn them into a more or less coherent story. The TV series is thus better than the books, though it only won by default.)

Example 3: Shakespearean Tragedy

The great tragedies are not all fantasy in the modern sense. Some have ghosts or witches, but not all. However, they are fantasy in the sense that they aren't realistic. Instead, they reflect our fantasies. They take place in a heightened reality, where people rise higher and have stronger, purer feelings than we do.

They are fantasy, not in the modern genre sense. They tell a fantasy of humans scaling the greatest of heights, only to then be brought to ruin by their flaws and errors. (I'm speaking about ancient Greek tragedy here too.)

Shakespeare was a guy who knew how to kill characters. In the best tragedies, the characters are developed and saved up in order to be liquidated in an overwhelming disaster. I mean, sure, you'll lose an Ophelia or two along the way to move things along and keep the audience alert.

You save up most of your characters for a truly epic disaster, to raise the emotional stakes as high as possible and try to send the audience out into the world truly affected. (What theatre nerds call "catharsis.")

(But when too much death happens, the story becomes nihilistic and the audience grows numb. I’m finding everyone-but-one-must-die stories, like Battle Royale and Hunger Games, increasingly distasteful. While Squid Game was very well made, it felt it had to slaughter hundreds of characters to affect the modern audience. Worrying. The death of one character we care about has more impact that mowing down hundreds of drones.)

Example 4: The Dead Master

I've talked a lot about the timing of character deaths, but I've said little about something just as important: The purpose of the death. For the death to have full effect, it needs to reinforce whatever is going on in your story.

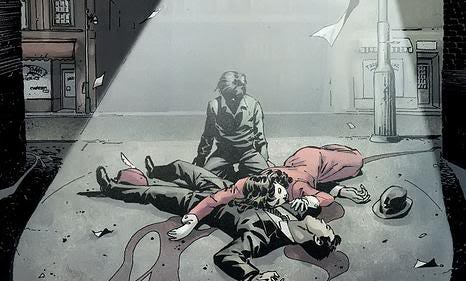

There are lots of ways deaths get used. One archetypal example: The loss of your teacher or parental figure. In Kung Fu movies, the hero is required to avenge the death of his master to the point of parody. (eg Pai Mei in Kill Bill. Oogway in Kung Fu Panda.) But there's also Obi-Wan and Yoda in Star Wars. Spiderman driven to heroism by the murder of his uncle. Mufasa in The Lion King. Batman after his parents are killed in Crime Alley.

This is so emotionally effective because it's a condensed version of Human Existence: Our parents and elders teach us. They die and leave us to continue their work. We pass down that knowledge to our children.

When evaluating how to use death in a story, it's important to not forget the most obvious thing: Death is the universal human experience. We all, at some point, gotta do it. When a character dies, we feel less lonely in this grim fact. If the death has meaning, this comforts us in the face of grim, unavoidable reality.

Writing Fiction Gives A Weird Sort Of Power

When a fictional character dies, it affects us. Our strange brains can feel great empathy for people who don't exist. Seeing these imaginary people die gives us a tiny, tiny fraction of real shock and real mourning. This must have some value to us, or humanity wouldn't have chased that sensation in fiction for thousands of years.

If your movie is about an epic battle, characters have to die. That is what a battle means. If nobody dies, your whole work becomes a lie. So, if you are going to kill characters, do it with maximum effect. Spread it out. Make it unpredictable. And be sure to save up a bunch for a really big finish.

The characters we create and control are powerful tools which can create strong emotions in our customers, for good and ill. We need to use this power responsibly. But, more importantly, we do need to use it well.

Spiderweb Software creates turn-based, indie, old-school fantasy role-playing games. They are low-budget, but they’re full of good story and fun. You can still late-back the Kickstarter for our next game, Avernum 4: Greed and Glory.

Two Thoughts and a Question:

1. I can't help but think of all the fantasy settings that almost immediately undermine death, just as a general concept, in their setting by making resurrection possible, or directly confirming the existence of gods/afterlife. That kind of thing just completely ruins the universality of death, the parallels in the fiction to our own Human Experience, and as a result cheapens every fictional death in the setting, whether the characters come back or not. There's something seriously wrong with your story, I think, if the common cold is tougher to get over than the a date with the reaper.

2. How do we reconcile making character deaths meaningful in an RPG with the fact that most (almost all) RPG systems are predicated on serial mass-murder? Sure, it's often the case that our "designated victims" are inhuman monsters, or contrived to be inherently evil to avoid the issue entirely, but it's still a *massive* amount of blood on our heroes'/players' hands, and I don't think I've ever seen an RPG where the "good guys" don't wind up having a higher specific body count than the "bad guys." Which isn't to say I don't think it's possible to write compelling and engaging death scenes with characters who've killed a lot, obviously that's not the case, but rather that there's the kind of weird tension in RPGs, specifically, where we're expected to care about the deaths of friendly NPCs/PCs, but not to think about our potential moral culpability in murdering 600 goblins or whatever.

Question: I'm curious what you think makes for more effective (friendly) character death: something pre-scripted, where the character(s) dies in a scripted and predetermined manner (EG Aeris in Final Fantasy 7), versus more reactive scenes, where the death is or can potentially be a consequence of the player's actions (EG Wrex in Mass Effect 1). Does giving the player agency in the scene make it more powerful, or does it rob the death of its power by enabling players to "game" the whole system and avoid the death entirely? Or better yet, a "Kobayashi Maru" scenario where the player's actions will lead to a deadly outcome no matter what they do, but *who* dies can vary based on what they do and/or random variables, making the meta-gaming goal not about evading the death, but about killing or saving one character over another.

The characters that died during the Red wedding were main characters in the first several books, but they were not main characters in later books.

You don't have to view the books as part of one grand series, with the same main characters.

And it's debatable whether some of the killed were actually main characters, for example Rob Stark, he didn't actually have any chapters focused from his point of view in any of the books—main character?? Probably not.