Why Video Games Are Tough For Storytelling

A good story can help your game make money, but the medium will fight you every step of the way.

"Players will forgive your game for having a story as long as you allow them to ignore it." - Vogel's 2nd Law of Video Game Storytelling

I recently wrote a blog post about writing good, clear stories that progress logically and make sense. It was based on a short, really good video by the guys who made South Park (and a bunch of other stuff).

The basic idea is this: When your story moves to another scene, the scenes should be collected by "Therefore" or "But then". They should never be connected with "And then."

As in, each scene should be the result of what came before. Someone does something to achieve a purpose. Someone else does something to react to that. And so on. This creates a logical story that moves at a good tempo towards a conclusion.

But I'm a video game guy. (Kickstarter for our next game running now!) What does all this mean for me?

It turns out the things that make a video game feel like a video game make storytelling very hard.

Storytelling In A Video Game Is A Strange Thing

I will go to my grave saying that, if you want to create a game that gets a following and makes money, good writing is the most cost-effective way to help. Good words and good settings are cheap to make, and they can massively increase the popularity of a product.

(This is why licensed games will always be a thing. If you took a Star Wars game and stripped out all of the Star Wars stuff but left the gameplay alone, the resulting game would sell worse. Words are selling it, even though it's just drafting behind a movie made by someone else in 1977.)

So what makes a video game story good?

Remember, I'm not an artsy-fartsy type. I care about games because they make me money I use to buy food. My definition of a good story is: It gets players more passionate about the game, which increases word-of-mouth marketing, which makes money.

I'm a cold-hearted mercenary.

I'm not going to make any blanket statements about problems I see in game stories: Flat characters. Generic settings. Nonsensical or forgettable stories. Sure, that happens a lot. But it's common for movies and TV too. As Sturgeon's Law says, "90% of everything is crap."

What I want to talk about is the friction in video games that keeps a story from engaging the player.

So Here's The Scenario

You are making a single-player game with some kind of story. For whatever reason, you want the story to be good enough to engage the player.

I think the real problem is that even when game stories do have good elements, they don't gel. They don't come together with the impact they should have. I just played Alan Wake, for example. That story has a bunch of cool ideas in it. Yet, when I got to the end, it left me feeling really 'meh.'.

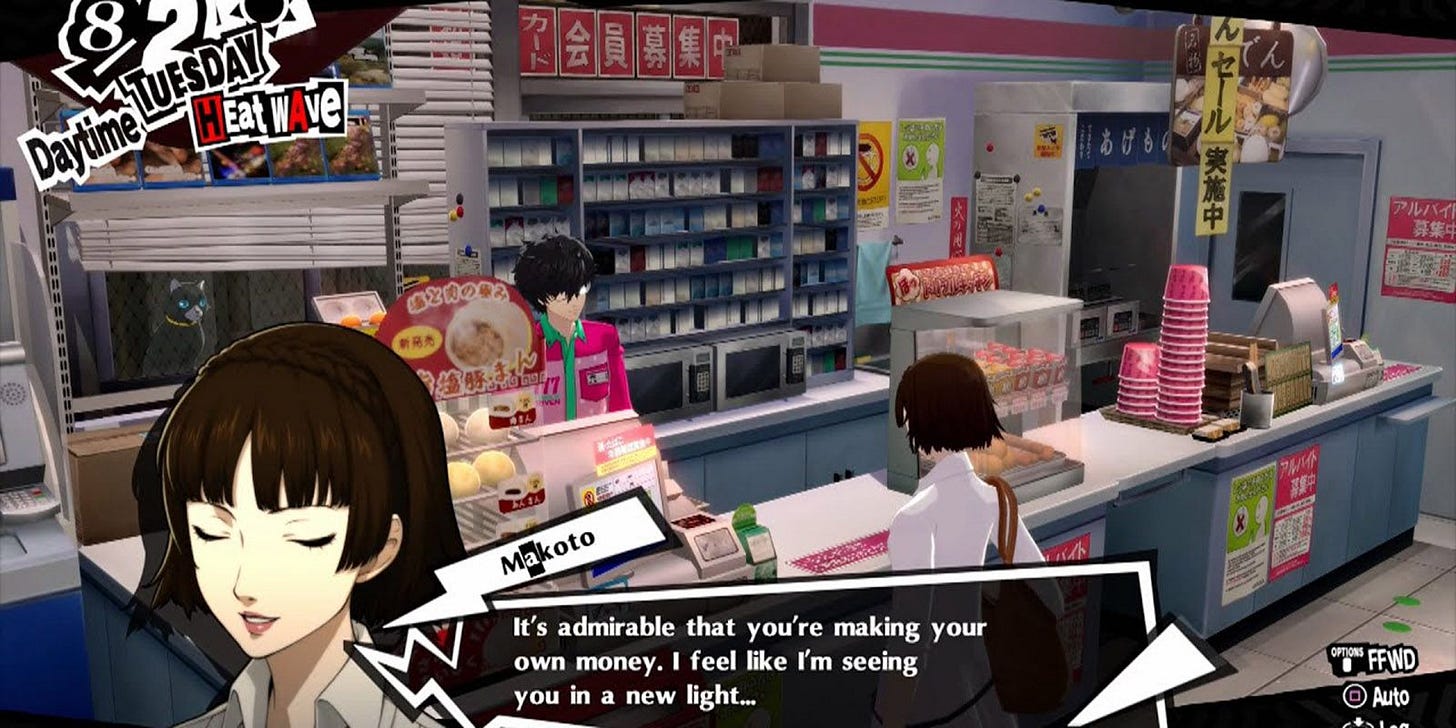

And I know I'm not going to get a lot of agreement on this one, but the story of Baldur's Gate 3 didn't make a strong impression on me. It did better than most. I actually followed the main plot, more or less, and I did enjoy the side character stories.

It's just that, in the end, it didn't really come together. The main story was a constellation of largely unconnected events in my mind. In the end I killed a big monster, but don't all RPGs end that way?

That is why most of the memeing of Baldur's Gate 3 was about the companions. The main story had a ton of stuff, but it was disconnected.

In my experience, this happens a lot.

Why?

Because the activities you actually do in a video game, in-between the cutscenes and the conversations, may be part of the story, but they don't move the story forward. There's no "therefore."

Suppose you're playing a single-player game with some kind of story. What do you actually do in the game?

1. Video Games Have Lots Of Training

Training is "And then" storytelling. You do the same thing. Shoot the same enemy, fight the same fight. And then you do it again. And then you do it again. And then. And then.

Training in movies and shows is almost always covered quickly, usually in the form of a montage. (Once again, Trey Parker and Matt Stone come through for us.) Showing a lot of the training would be death for your movie.

There are movies that make training interesting, but the training has to be the whole plot, with characters struggling against some sort of obstacle. The highs and lows of the process give the story a logical flow toward a conclusion.

But in video games? The training/leveling is meant to be the fun. Which is fine, except that it pulls all focus away from your story.

2. Video Games Have Farming: Loot/Weapons/Keys/Plot Tickets

Conan starts his movies already having a good sword. John Wick gets his gun by digging in the yard for about 30 seconds of screen time.

In a fantasy RPG (even one of mine), you are threatened by an enemy, THEREFORE you get your sword. OK, fine. And then you get a better sword. And then you get a better sword. And then. And then.

Farming has exactly the same issue, but it's more boring.

Then there's "plot tickets". This is just an arbitrary item you need to get farther into the plot. Like you need to fight Archduke Bob. So you need to sneak into his castle through the sewers. If you need the Ruby Key to unlock the sewer door, that's a plot ticket.

The difference between a "Therefore" scene and an "and then" scene is that you can cut the second sort of scene and not hurt the story.

In your story, the sewer doesn't HAVE to have a locked door. You added the Ruby Key as a plot ticket. "You have to fight Bob, therefore you enter the sewer. And then you find you need a key."

Video games (including mine) lard on plot tickets because it pads out the game (not great) and gives the party the chance to train in another dungeon (which can be fun but it is unrelated to the story). By the time the players are done getting the key, do they even remember who Bob was?

There are successful movies that require the hero to gather a bunch of plot tickets to proceed. Indiana Jones did a side quest to find the location of the Ark of the Covenant. Harry Potter needed to destroy seven horocruxes. (SEVEN!)

You can have a few plot tickets. That's where the genius is. Indy's side quest to find the ark's location led to a really exciting scene with snakes. But you can't get away with too much of this. Every moment he spent in that tomb finding where the Ark is gave the audience time to forget why he was looking for it in the first place.

And Harry needing to find SEVEN baubles to break in those intensely over-padded books mainly shows that J.K. Rowling really needed an editor who could stand up to her.

But in video games? The plot tickets are the point. They are expected. You have to have SOMETHING to do, so that you can grind down trash monsters and get loot and experience. It's not a bad thing, except that players expect a lot of it and it can crowd everything else out.

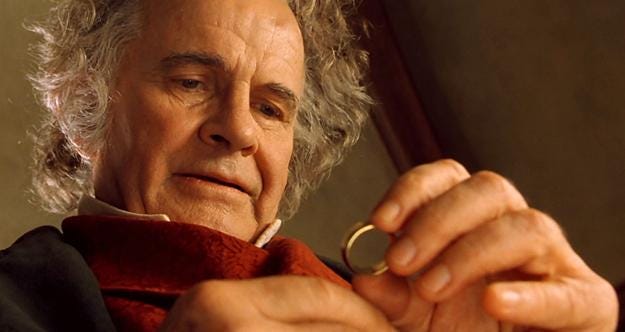

But it’s not necessary for a story. Remember that the most famous magic item in all of fantasy, the One Ring of The Lord of the Rings, just starts the series in the pocket of a guy in town. That guy stumbled upon it by mistake in another book. How you get an item is less interesting than what you do with it.

3. Video Games Have Travel

Travel in stories is boring. The real action in a story happens when you get to your destination.

The Lord of the Rings is largely a book about traveling and journeys. Yet, most of the actual travel happens offscreen/offpage. When the books do describe the travel, it's to give very dense information about setting and characterization. A page or two at most, then, "They hiked two weeks to get to the exciting place."

Star Wars made it even easier for the screenwriters. All the journeys were through hyperspace. Five seconds of pretty lightshow covers it. Very efficient.

But in video games? When you travel, you TRAVEL. Every step of the way. This is necessary. The journeys are where the action takes place: the fights, the sneaking. The journeys are where the experience is farmed to gain levels. So many games are just about the challenge of travel.

And hey, travel in video games is fun. Most of Souls like games are winding your way through a cool lethal maze. That's the game. And it's a blast. These games are not about story, though.

Consider The Last of Us, a game widely acclaimed for its story. It only has one section lots of people complain about: A long, LONG sneak through the ruins of Pittsburgh The game gets us to really care about these characters, and we get kept from them by this grind of "Another shadowy passage full of zombies. And another." This is a great example of a game trying to do good storytelling but it gets eaten by the game part.

Being A Video Game Dilutes The Story

To be very clear, I am not advocating for the removal of leveling and travel in video games. I do not want every game to become a twee two hour mini-movie. If I want to see a movie, I'll just watch a movie.

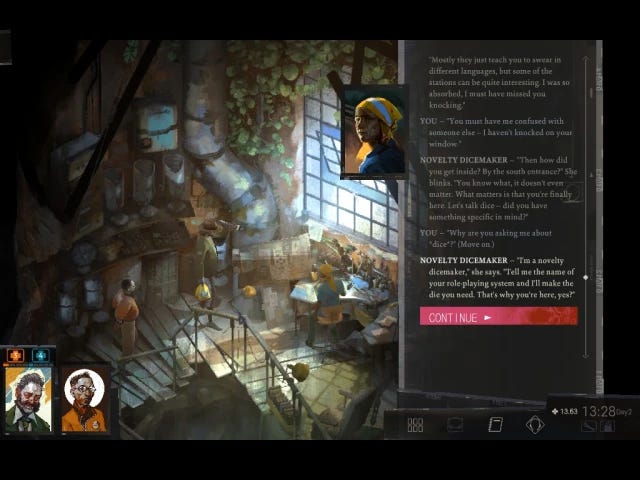

You can have a game that tells a very focused story by trimming all this game stuff out. The best example of this: Disco Elysium. It's an RPG that's almost pure storytelling, and it's fantastic. Yet, very few people want every game to be Disco Elysium. One a year sounds about right.

If you ever played any of my RPGs, you'll know how I feel. My games have a ton of story. But also lots of travel and leveling and finding plot tickets. I LIKE the stuff that makes games be games.

However, you do have to be honest about their qualities. Different sorts of content have advantages and disadvantages. The secret is figuring out how to balance them.

Video games should be allowed to be video games. But if you have storytelling as a goal, there are better and worse ways to do it.

Next Week I'll give some of my ideas for how to do that, with practical advice for how to make more money in this business.

Spiderweb Software creates turn-based, indie, old-school fantasy role-playing games. They are low-budget, but they’re full of good story and fun. We are doing a Kickstarter for our next game, Avernum 4: Greed and Glory. We hope you take a look!

I don't think it's too much of a hot take to say that the main quest of BG3 wasn't the most compelling. It serviced ferrying you around and let you enjoy its solid gameplay and great companions. It's very much a 'the sum of its parts is greater than you'd expect'. But also as you say, if the story didn't exist _at all_ BG3 wouldn't be particularly motivating. I think it did something very right by creating memorable and compelling characters in a variety of personalities so that the ones certain people hate other people love.

Mass Effect 2 remains one of my favorite games even though it's main plot is best described as 'and then nothing really happened and now Mass Effect 3 has to do all the heavy story lifting' because it was a fun 'assemble the team' game where you're showcased a lot of interesting characters and you can bring them along places and see them comment on things. Compelling characters can make you really interested in going along with an otherwise completely unremarkable plot.

To bring it to your own game series, a huge part of why I enjoyed Queen's Wish was because of 'my fantasy family'. You didn't interact with them all the time but they were a constant presence and they had personality and I wanted to feel like I could budge and influence them while still doing right by them. The overarching plot of the game isn't particularly complicated or twisty compared to Avadon, but the characters scattered in the world made it feel real and made me feel a lot more connected with the weight of the actions I was taking.

I think it's fair to assert that every CRPG owes its existence to D&D. So when it comes to storytelling in a CRPG, or any video game that claims to have a story, one can compare a video game designer to a D&D dungeon master.

Some DMs "railroad" their players through a pre-planned story. The players do not have agency in how the story turns out. Any activity they perform is a mechanical exercise (combat, skill checks) that prompts the DM to tell the next segment of the story they wrote. It's effectively a Choose Your Own Adventure book that the DM is reading to you.

On the other extreme, some DMs create "sandbox" environments. There may be pre-planned or ad-hoc events that present challenges, but the outcome, order, etc. of what happens is through player agency. There is essentially no story planned out at all. The players are creating their own story through their actions and reacting to events thrown in their path to keep them busy if they can't think of anything else better to do.

I think when gamers say they want a good story, they're saying they want to *feel* something in what they are doing. If there's no emotional or intellectual payoff, then the story is no good. If the events in the game tug at your emotions or reinforce how smart you are, then you'll have a positive opinion about it. The twists and turns of unexpected events or revelations and the payoff of seeing how they resolve are intellectually stimulating, and the tug of seeing places or characters you've invested in succeeding or failing is emotionally stimulating.

A good CRPG provides plenty of player agency while still throwing them a curveball with unexpected events or revelations. A bad CRPG either railroads the player through a predetermined sequence of events, or it dumps a "clean the map" job at their feet with no surprises or emotional investment.